UI Researcher’s Work Reveals Pattern in Earth’s Copper Deposits

About 75 percent of the world’s copper comes from porphyry copper deposits. A new study from the University of Idaho and the University of Michigan unearths how these economically valuable deposits are distributed around the world.

The research, published in May 2015 in Nature Geosciences online, indicates that climate helps drive the erosion process that exposes porphyry copper deposits, as well as helps determine where on Earth the deposits form.

The study was conducted by Brian Yanites, an assistant professor in the UI Department of Geological Sciences, and Stephen Kesler, an emeritus professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Michigan. Yanites is a geomorphologist, studying the Earth’s topography. Kesler is an economic geologist, studying the formation of deposits that can be mined for raw materials.

“This is the first time that we’ve found a connection between geomorphology and economic geology,” Yanites says. “It’s exciting to think that erosion and the building of our mountain landscapes influences where society gets its resources from, and it’s another line of evidence of the importance of climate in the shape of the landscape.”

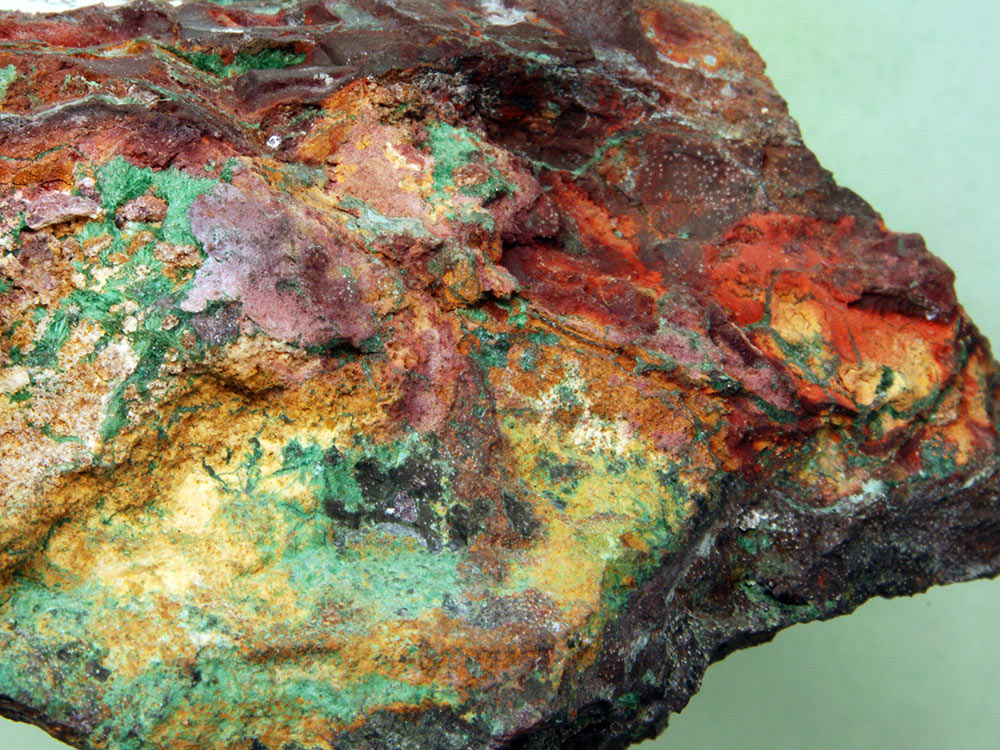

Porphyry copper deposits initially form beneath volcanoes, on average 2 kilometers below the surface. Over the course of millions or tens of millions of years, erosion exposes them.

Yanites and Kesler examined data on the age, depth and number of exposed porphyry copper deposits in regions around the world. When they compared these data to the regions’ climates, they noticed a pattern: The youngest deposits are found in areas of high rainfall, such as the tropics, indicating rapid erosion. Deposits are older in dry areas, indicating low rates of erosion.

They then counted the number of deposits in the different regions and found something striking: Where erosion is rapid, there were relatively few deposits, but locations with low erosion rates contain a high density of deposits. Such regions include the Atacama Desert in the Andes Mountains and the American Southwest — both places where porphyry copper mining is important to the economy.

The researchers developed a simple model to explain the relationship between erosion rate and the number of deposits in a region. Yanites compared it to a game on the TV show “American Gladiators,” where competitors had to run past tennis-ball launching cannons to reach their goal.

“The faster the competitors run, the lower the chance that they will get hit because they spend less time in the ‘danger zone,’” Yanites says. “Similarly, rock layers that spend less time in the porphyry production zone — due to rapidly eroding landscapes above — have less of a chance of getting injected with one of these valuable deposits.”