Catching Up with CALS — Feb. 19, 2025

Dean's Message — Capitalizing on Transfers

Only 11% of Idaho community college students go on to earn a bachelor’s degree within six years of receiving an associate degree. However, once a community college student succeeds in making the transfer to a university, that student’s odds of earning a bachelor’s degree surpass the general population of university undergraduates. These surprising facts highlight an opportunity for the University of Idaho and its College of Agricultural and Life Sciences (CALS), and they explain why we’re stepping up our efforts to ease the transition for community college students who are interested in our programs.

Between 150 and 200 students transfer annually to U of I from Idaho’s four community colleges — College of Southern Idaho (CSI), College of Western Idaho (CWI), College of Eastern Idaho (CEI) and North Idaho College (NIC). In 2024, U of I hired Todd Schwarz, who previously served 11 years as CSI provost, to a newly created position tasked with increasing our transfers through a student-centered approach. Transfers to U of I have declined by 14% across the board since 2019, much of this due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Schwarz, special assistant to the provost for community college engagement, has set a goal of restoring transfers to pre-COVID levels, which would bring in roughly $1 million in additional tuition. Schwarz recognizes that community colleges are more likely to educate first-generation or nontraditional college students, many of whom can’t lean on parents for guidance or financial support. It’s incumbent upon U of I to bridge that support gap with advice, encouragement and financial aid. “It’s important that the mindset is about students and what’s best for them and not just generating enrollment,” Schwarz explained, emphasizing U of I is already doing an excellent job and has the highest success rate of achieving transfers of any four-year public school in Idaho. “It’s not just about transfers. It’s about processes to make it as simple and seamless as possible for students to make that jump.”

A few barriers are preventing Idaho community college students from pursuing four-year degrees. The first is geography. For example, CSI, located in the Magic Valley at the heart of Idaho’s dairy and food processing industries, is ideally situated for students interested in pursuing careers in agriculture. The CSI campus, however, is a roughly 450-mile drive from U of I’s Moscow campus, and few nontraditional students have the luxury of moving so far away from home. Alignment of curriculum is another barrier. Community College students may be discouraged if their general education courses don’t meet U of I requirements and therefore aren’t counted towards requirements of a bachelor’s degree.

U of I and CALS are taking steps to address some of these stumbling blocks. We’re emphasizing programs that enable students who start at a community college to finish degrees by taking U of I courses offered remotely. Within CALS, the primary example of this approach is our remote agricultural science, communication and leadership (ASCL) degree. Amanda Moore-Kriwox, CALS program specialist, facilitates the program from her office on the CSI campus. Participants complete two years of classes from another university or two-year program and take CALS distance-learning courses for the final two years of the degree. The remote program typically boasts an enrollment of between 15 and 20 students. Furthermore, out-of-state students who take remote courses through U of I are eligible for in-state tuition rates. Program graduates land jobs in a broad range of agricultural fields, such as agronomy, crop research, sales, commercial lending and water management. ASCL requires a capstone internship, and graduates often accept their first full-time jobs with the same employer who hired them as an intern.

U of I has signed articulation agreements with the state’s five community colleges establishing transfer pathways, ensuring community college courses meet the university’s standards and transfer students have a clear path toward earning a bachelor’s degree as a Vandal. At CSI, for example, 11 majors have articulation agreements in place. CALS has two majors with established CSI articulation agreements — ASCL and agricultural economics. I see another prime opportunity to accommodate transfers from eastern Idaho through a new collaboration with Brigham Young University-Idaho in Rexburg, where we’re promoting a three-plus-one program in agricultural education. The future is also bright regarding collaborations with CWI, where I’ve had the chance to tour a state-of-the-art facility under construction that will host their agricultural business and leadership, fermentation science, meat and animal science and horticulture and technology programs. CALS faculty must forge relationships with CWI’s agricultural instructors and make certain those developing programs align with our requirements and that we can lend our expertise to broaden educational opportunities for Treasure Valley students.

We face fierce competition in our efforts to maintain and grow enrollment in a state with a population of 1.965 million. Yet training students is our mandate, and we’ll need to be creative in our recruiting efforts to ensure our continued prosperity. By strengthening our ties with Idaho’s community colleges, we’re taking a small step toward meeting that challenge while also serving Idahoans where they live, deepening our state’s labor pool and strengthening our institution’s well-established statewide presence.

Our Stories

Liming Trials

Separate University of Idaho research projects conducted over several years in eastern Idaho and northern Idaho have both concluded applying lime to raise soil pH can be a cost-effective approach toward improving crop yields.

Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist Jared Spackman, a barley agronomist, has been conducting laboratory experiments and trials in eastern Idaho commercial farm fields since 2021 aimed at developing recommendations to help the region’s farmers optimize the timing and volume of lime applications to best fit their management practices, climate and soil type.

In northern Idaho, Kurt Schroeder, an associate professor and Extension specialist and cropping systems agronomist is entering his ninth year of lime-application research. He’s found that most farmers in his region who are losing yields due to acidic soils stand to recoup their investment in a lime application within three to nine years, depending on the tonnage of lime they’ve used.

In chemistry, pH — short for potential of hydrogen — is a logarithmic scale ranging from zero to 14, in which seven is neutral, lower numbers represent acidity and higher numbers denote alkalinity.

Fertilizer applications, nutrient leaching caused by rainfall or irrigation, the harvest of high-yielding crops and the loss of soil organic matter can contribute to acidifying fields, thereby stunting root development of crops and limiting yields. Amalgamated Sugar Co. generates large volumes of lime as a byproduct of refining sugarbeets and supplies the material to many eastern Idaho growers, most of whom apply it to acidic fields every five years.

“What really got this study going is growers were telling me they apply anywhere from 1 to 4 tons of lime per acre, but they really didn’t know if that was the right amount or how long it lasted,” Spackman said. “Do our soils perform the same as the other soils around us or in the Midwest? The eastern Idaho calibration has never been done as far as I can find.”

Aluminum — which is toxic to plants, causing root damage and interfering with normal growth — becomes soluble in a form plants can absorb in acidic soils. Free aluminum and iron bind to soil phosphate reducing phosphorus availability to the crop. Nutrients including potassium, calcium and magnesium may also leach out of acidic soils further reducing soil pH. A pH of 6 to 6.5 is conducive to growing most crops. Yields begin to decline when soil pH is below 6 for alfalfa, 5.4 for barley and 5.2 for wheat.

Spackman has offered eastern Idaho growers who apply lime a few general guidelines based on his research thus far.

“Eastern Idaho’s acidic soils that start out at a pH of 5 to 5.4 will likely benefit from 2 to 4 tons of lime per acre and will rapidly remediate soil up to a pH of 6 to 6.5 in the top 6 inches, and the effects will likely last three to six years before another lime application is required,” Spackman said. Spackman started the study with a $75,000 grant from the Idaho Wheat Commission, covering research from 2021 through 2023. Two years into the project, he obtained $50,000 from the Idaho Barley Commission and $75,000 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Western Sustainable Agriculture, Research and Education (SARE) program, funding liming research through 2026.

In addition to on-farm field studies, Spackman is conducting laboratory experiments. He collected samples of acidic soils with different textures from commercial farm fields in Fremont, Power and Caribou counties in eastern Idaho — as well as Latah County in northern Idaho for comparison. He applied lime in the form of pure calcium carbonate to the potted soil samples at rates ranging from the equivalent of zero tons per acre to 8 tons per acre and recorded how the pH responded in soils with textures of loamy sand, silt loam, loam and clay loam.

Spackman also applied lime at different rates to strips within four commercial fields in both counties in 2021, asking landowners to continue farming them as usual. He applied lime to strips in five additional commercial fields in 2023.

In those strip trials, pH changes have tended to last longer in clay soils, but it’s taken more lime to raise the pH. Spackman advises applying lower rates of lime more frequently on sandy soils. He’s observed in his strip trials that it may take two to three years for liming to significantly improve yields.

Soil moisture is needed for lime to affect pH, making the optimal time to apply lime, especially on dryland farms, during the fall before the winter snowpack accumulates.

Many farmers associate problems with certain weeds with low soil pH. Spackman conducted a greenhouse study in which he planted several weed species in pots of varying pH levels and soil types to determine if a lower pH invigorated any of the weed species. Having noticed no difference in weed growth across pH levels, he plans to have an intern conduct a new study next spring, planting both weeds and barley plants in common pots. Spackman hypothesizes that the combination of a lower pH and competition with weeds that aren’t affected by pH changes will severely stunt barley growth.

In a survey of 125 fields across eight northern Idaho counties conducted a decade ago, Schroeder and Doug Finkelnburg, an area Extension educator and cropping systems agronomist, concluded 75% of fields had a pH of 5.2 or below in the top 6 inches of the soil and were at risk of developing issues with aluminum toxicity. Schroeder believes soil acidity is beginning to “nibble away” at yields in his region, and many growers have simply stopped planting sensitive crops such as barley in the most severely impacted fields.

Schroeder has documented increases in soil pH and consistent yield improvements where he’s applied lime, even eight years following the initial application. He’s noticed benefits beginning in the first season following fall lime applications and in the second season following spring lime applications.

Schroeder recently reviewed all his trial data and presented the results to a large group of growers and agronomists during a workshop, Liming for Long-term Gains, hosted Dec. 16 in Moscow.

The average winter wheat yield gains resulting from liming were 12% per year at the 1-ton rate, 16% at the 2-ton rate, and 19% at the 3-ton rate. In spring wheat, yield gains have averaged 11% at the 1-ton rate, 18% at the 2-ton rate and 24% at the 3-ton rate. Eight years following lime applications, Schroeder reported he’s still seen no evidence of soils in any of his trials reverting to their pre-liming acidity.

“We were expecting maybe by six to seven years we’d start to see pH start to decline again. We’re not seeing a clear trend of that happening,” Schroeder said.

Lime is incorporated within the top 6 inches of soil and doesn’t appear to move through the soil profile. Within the top 3 inches of soil where Schroeder has applied lime in his trials, soluble aluminum is essentially eliminated, and it’s reduced by three-fourths at 3- to 6-inch depth.

Schroeder advises his region’s growers experiencing challenges with acidic soils to diversify soil rotations, including legume crops, and implement variable-rate nitrogen applications in addition to liming. The cost of buying and transporting lime in northern Idaho, the fact that most farmers lack the equipment to spread lime sources and contractual challenges of applying lime on leased cropland all pose barriers to using lime as a tool in the region.

Spackman’s research is funded through 2026 with $75,000 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Western Sustainable Agriculture, Research and Education (SARE) program under award No. OW23-382. The federal share represents about 38% of the total funding.

Beef 201

University of Idaho’s beef team is accepting applications for another multi-day workshop tailored toward helping the region’s beginning ranchers succeed.

Beef 201: Beginning Rancher Development is scheduled for May 19-21 in Moscow, funded with a three-year, $479,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. It follows beginning-rancher workshops hosted on campus through the grant last May and July.

“We’re trying to serve beginning farmers and ranchers in the Northwest to help them kick off their business as a rancher or just help them to expand or improve their profitability,” said Phil Bass, associate professor of meat science who serves as the grant’s principal investigator.

In response to participants’ feedback, the upcoming workshop will explore cattle breeding, health and genetics more in-depth than last year’s workshops. Ranchers who participated in one of the 2024 workshops are encouraged to attend this spring, as the content shouldn’t be duplicative. The name Beef 201 references the workshop being in its second year rather than the level of difficulty, which should be comparable with the initial two workshops in 2024.

Dr. Lauren Christensen, a licensed veterinarian and assistant professor specializing in mixed practice production medicine, will present for nearly a full day on livestock health. While last year’s workshops included intensive training in beef fabrication, that portion will be scaled back, encompassing basic identification of popular retail cuts.

“Beef fabrication has the tendency to draw the crowd in. They’re very curious, but it’s not really helping their business,” Bass said. “We need to back off on the meat so we can focus more on the raising of the cattle.”

The cost of the workshop is $20 and will include lunches, snacks and beverages. Participants also receive tools to use on their ranches, such as halters, sorting sticks and thermometers. Scholarships are available to help participants cover mileage, hotels and other travel costs.

The team planned to host a single multi-day workshop in May last year but opted to schedule a second one in July based on demand. Bass also anticipates hosting a second, multi-day workshop this summer, if demand necessitates it.

Participants in Beef 201 will have the opportunity to have soil and forage samples from their operations analyzed, and experts from the meat science team will be available to travel to their individual operations and make assessments. New ranchers may also be paired with experienced mentors in the industry.

Additional grant funding has been used to purchase teaching tools and props, such as a replica cow used to demonstrate fetal dystocia, which occurs when abnormal fetal size or positioning complicates delivery.

The grant is also funding several smaller same-day workshops throughout the Northwest.

Looking ahead, Bass hopes to use grant funding to hire a leading business management school for ranchers, Ranching for Profit, to host a two-day in May of 2026. Ranching for Profit would be offered on campus within the college’s forthcoming Meat Science and Innovation Center Honoring Ron Richard. The state-of-the-art abattoir is currently under construction.

U of I’s Beef 201 team also includes meat science Associate Professor Michael Colle, UI Extension educators Jessie Van Buren, Meranda Small, Audra Cochran and Brett Wilder.

3-Minute Thesis Winner

Rita Franco, a University of Idaho doctoral student studying nutritional sciences, chose to leave her native Guatemala and continue her education in the U.S. in part because she wanted to improve her English-speaking skills.

She’s checked that box in a big way.

On Feb. 11, Franco placed first in the Idaho Statewide 3-Minute Thesis contest, which is a public speaking competition in which participants are tasked with presenting their research to live and virtual audiences in three minutes or less.

Franco, who is studying under Assistant Professor Ginny Lane in the Margaret Ritchie School of Family and Consumer Sciences, faced 11 other graduate students from U of I, Boise State University and Idaho State University during the contest, hosted at the Bennion Student Union Building at U of I Idaho Falls. She also won the People’s Choice Award and took home $2,500 in prize money.

She qualified for state by finishing second and earning the People’s Choice Award during U of I’s 3-Minute Thesis contest, hosted Nov. 14 in the Pitman Center, and she will now move on to compete against winners from 14 western states in Colorado.

“Winning this kind of competition in a country that is not yours, in a language that is not ours, it’s so meaningful,” said Franco, whose long-term goal is to generate scientific evidence for decision-makers to use in developing food-security strategies. “It’s giving me more confidence. It’s made me feel that I can do more things.”

Her talk, called “Improving Child Nutrition Through Household Poultry Projects in Guatemala,” describes her research under Lane analyzing the dramatically improved health outcomes among rural Guatemalan children who consume at least one egg per day.

Franco came up with a memorable introduction to hook an audience: “So I’ve heard that people in the United States say, ‘An apple a day keeps the doctor away.’ But in Guatemala, my home country, we must say, ‘One egg a day keeps the stunting away.’”

In her brief speech, Franco describes how Lane started the egg nutrition project in 2019, providing chicken coops to families in rural Guatemala and guidance to help them raise eggs to supplement their diet and sell commercially. Lane and her research team recorded data on the overall wellbeing of the children of 10 families who were raising eggs through the study and returned for follow-up testing of the children over the course of six years. The researchers concluded children who regularly ate eggs were far less likely to suffer chronic health problems and stunted growth and development.

“In those communities, around 60% of children under 5 are stunted, and stunting has a lot of impact in a child’s life,” Franco said. “It reduces learning capacity. Children who are stunted will not have good grades in school, and in adult life they probably can only work in crops.”

Franco’s talk also cites recent economic data from the World Bank, finding every dollar invested in combatting malnutrition returns $23 worth of benefits.

“I think my main objective would be to create this evidence and to advocate to society, local authorities and donors to invest in nutritional projects,” Franco said. “I am trying to create this evidence to guide what people who make the decisions can use to improve their strategies.”

Taking an eight-week special-topics course designed to help structure and practice 3-Minute Thesis presentations was key to Franco’s success.

”I believe incorporating courses like this is highly beneficial for all graduate students, as it enhances our ability to communicate complex concepts effectively,” Franco said.

For her doctoral dissertation, Franco has been working under Lane to understand the reasons why Southern Idaho Latinos suffer from diabetes at much higher rates than other ethnic groups. The problem is especially acute among Latina women, who are 17% more likely to contract diabetes than white women.

“One of the important things the women mention is they don’t have time to have a healthy lifestyle because they work, and they also have to take care of their family. They don’t think about themselves,” Franco said.

In Guatemala, Franco served for two years as coordinator of an entity that advised the government on social welfare programs. She also worked for nonprofit organizations in her country, including serving seven years with World Vision Guatemala.

After earning her doctorate, Franco intends to return to Guatemala and devote herself toward lifting rural residents out of poverty.

Faces and Places

CALS Dean Michael Parrella was honored Feb. 18 at the Larry Branen Idaho Ag Summit in Boise with the renaming of the Governor’s Awards for Excellence in Agriculture Education/Advocacy award in his name. Parrella was also presented with the award. Also during the summit, retired CALS Director of Government Affairs and External Relations Brent Olmstead received the Marketing Innovation Award and U of I alum Bill Flory, '77, received the Technical Innovation Award.

Members of the Student Idaho Cattle Association (SICA) attended the 2025 Ag Seminar and Beef School held by the Bonner and Boundary County Cattle Association. Professor Joseph Kuhl has been named acting head of the Department of Plant Sciences.

Anthony Gonzalez, a senior from Rigby studying apparel, textiles and design, was invited to attend the Latah County Human Rights Task Force Martin Luther King Jr. Community Human Rights Breakfast, where he was presented the Rosa Parks Human Rights Achievement Award.

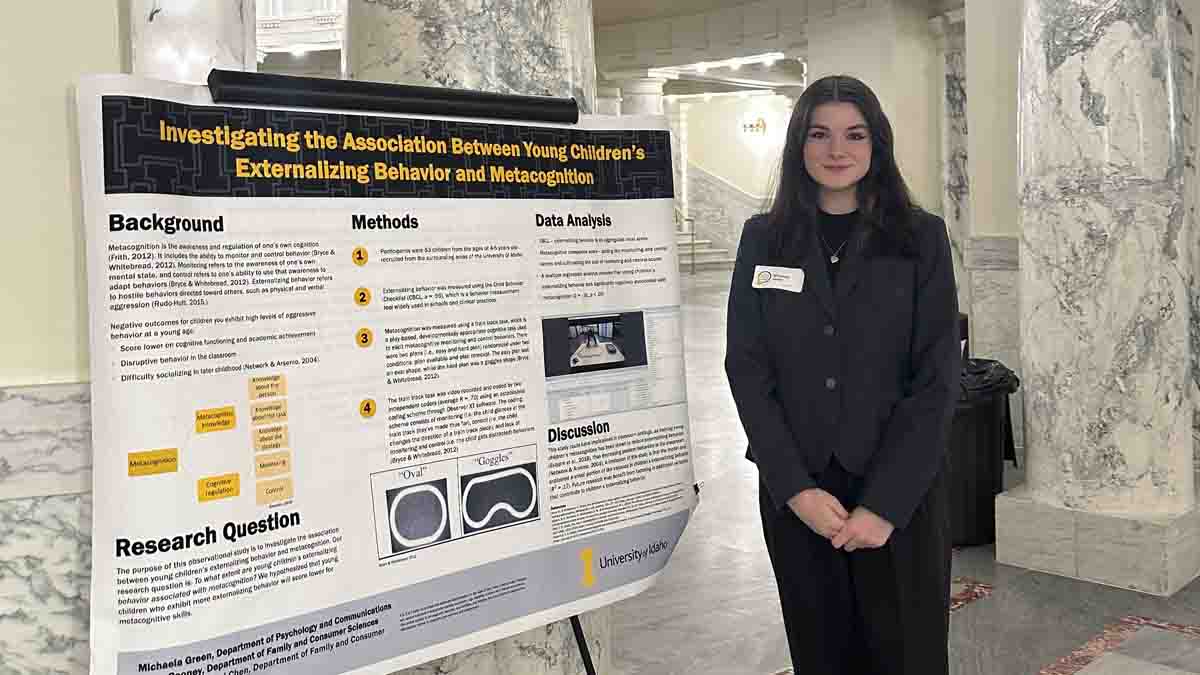

Michaela Green, an undergraduate research assistant working under Assistant Professor Shiyi Chen, recently participated in the U of I Legislative Ambassador Program, where she had the opportunity to showcase her research at the Idaho State Capitol on Jan. 29. Her project is entitled “Investigating Association Between Young Children’s Externalizing Behavior and Metacognition.” Green will also accompany Chen to present her study at the 2025 Society for Research in Child Development conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota, this April.

The Idaho and Malheur County Onion Growers Association inducted Professor Mike Thornton, with the Department of Plant Sciences, into the Idaho-Eastern Oregon Onion Hall of Fame on Feb. 4 during their annual meeting in Ontario, Oregon. Thornton, who will retire on March 31, was chosen based on his body of research benefiting the onion industry.

The Water Priority Extension Theme (Water PET) and the Idaho Water Resources Research Institute (IWRRI) are developing a list of Extension educators and specialists with skills, expertise or teaching experience in any water topic. IWRRI’s new strategic plan calls for strengthening U of I as the premier water research and education entity in support of Idaho’s communities. UI Extension professionals are encouraged to complete a brief, three-minute survey by the end of February to help develop the list.

Events

- Feb. 19, March 19, April 16 — 2024-2025 Heritage Orchard Conference, Online

- Feb. 20 — Virtual Food Safety Program: Dehydration Basics, Online

- Feb. 25 — Our Gem Speaker Series: Water Quality Trends Guide Remediation (Lauren Zinsser), Online

- March 4 — Free Virtual Pesticide Applicator Training, Online

- March 4, 11, 18, 25 — Spring 2025 Farm Financial Analysis class (pdf), Online