Undergraduate Plans to Use Chemistry to Reform the Legal System

Senior Lilian Bodley, 21, wants to use her knowledge of chemistry to change how people view and act on forensic evidence.

“A lot of people watch CSI and think that forensics is something it isn’t,” says the Caldwell, Idaho native.

Bodley wants to use her chemistry degree to show that forensics, or the scientific analysis of physical evidence, isn’t as simple as many people believe. On many TV shows, the police find DNA and they hand it over to the forensics expert who immediately matches it to the killer. In the real world, says Bodley, it is much more complicated. For example, many people assume that DNA analysis can happen in the span of an afternoon, but the process is actually long and expensive.

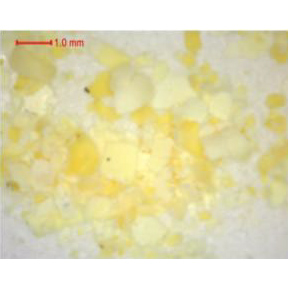

Besides the usual chemistry lab work that is required for a career in forensics, Bodley also studies archaeochemistry. For this, Bodley analyzes unknown materials inside historical artifacts from a variety of archaeological sites and museum collections across the United States and Canada. Her work in archaeochemistry has given her the opportunity to learn valuable analytical techniques as it relates to chemistry and history. She doesn’t just run a test and get a result; she has to place the result in the historical context of the artifact itself in order to find the answer.

Like archaeochemistry, forensics also must be placed in an outside context, meaning does the evidence make sense considering the crime scene, weather, the type of insect present in the area, etc. However, the ability to analyze evidence within its environmental context is not the only skill needed for forensics to be effective.

The Lab Report Chemistry

Ray von Wandruszka

Department Chair & Professor

Renfrew Hall 116 & 331

208-885-4672

Not accepting graduate students

Research: Humic materials; Archaeological chemistry

View Ray von Wandruszka's profile

According to Bodley, both basic science and forensic science must be well understood for a forensic scientist to analyze and present the various types of evidence. Bodley wants to use this understanding to help the general population better comprehend what forensics actually entails. This includes helping citizens, many of whom will serve as jurors at some point, understand that forensic evidence has certainties and limitations.

Many forensic techniques rely on pattern matching disciplines, like bite marks, hair analysis, shoe and tire prints or fingerprints. Though these are the most common techniques used by forensic experts, often evidence based on these procedures is introduced in trials without any real scientific justification. Bodley found out after speaking with several forensics experts that often courts rely on precedence that are based on antiquated evidence procedures, meaning that today’s cases can be judged using scientific techniques from over one hundred years ago.

According to Bodley, having a knowledgeable medical examiner, or updated legal precedence for evidence, or even one jury member who understands the realities of forensic evidence, could make the difference in whether or not an innocent person is convicted. A forensic scientist must be able to provide authoritative and scientifically accurate testimony that doesn’t mislead juries.

“It’s important to realize that forensic science is fallible, but it can do great things. I want everyone to see that,” said Bodley.

By Christi Stone College of Science

October 2019