Moose Seeing Winter Tick Uptick

Student Maps Winter Tick Loads on Idaho Moose

Riley Robenstein grew up in a rural neighborhood on the southeastern edge of Boise where coyotes yodeled, owls burrowed and hawks screeched over the sage brush landscape that mountain lions roamed.

It wasn’t akin to an episode of Animal Kingdom, but for a child, Robenstein’s upbringing was enough to impress her future.

“I have a strong appreciation for the sage brush steppe landscape,” Robenstein said.

She knew one day she would attend University of Idaho and, at least for a while, leave behind the wide open and windy plains of her southern Idaho neighborhood.

Robenstein didn’t consider, however, that once at U of I’s Moscow campus she would join a wildlife biology lab and be immersed in the study of ticks.

“Wasn’t on my radar,” the junior wildlife major said.

For almost two years, Robenstein has been learning about winter ticks — the kind that may be harming some of Idaho’s moose populations — as part of a moose and tick study in the lab of Janet Rachlow, professor of wildlife ecology, where Robenstein is among researchers exploring why moose numbers are declining in parts of the Gem State.

Robenstein wanted to know which regions of Idaho had the most winter ticks, which infest moose, spread disease and may weaken animals during winter and spring, the hardest time of year for the big ungulates. Moose with high tick numbers diligently rub infected areas to relieve the itching the ticks cause, breaking off hairs, or they rub their fur completely off, Robenstein said. The white appearance from hair loss and breakage cause biologists to refer to them as “ghost moose.”

Future research will examine what specific habitat type supports ticks, the locales where moose pick up the ticks that cling to them throughout the winter — hence the name winter ticks — and what measures may be taken to reduce this sometimes fatal interaction.

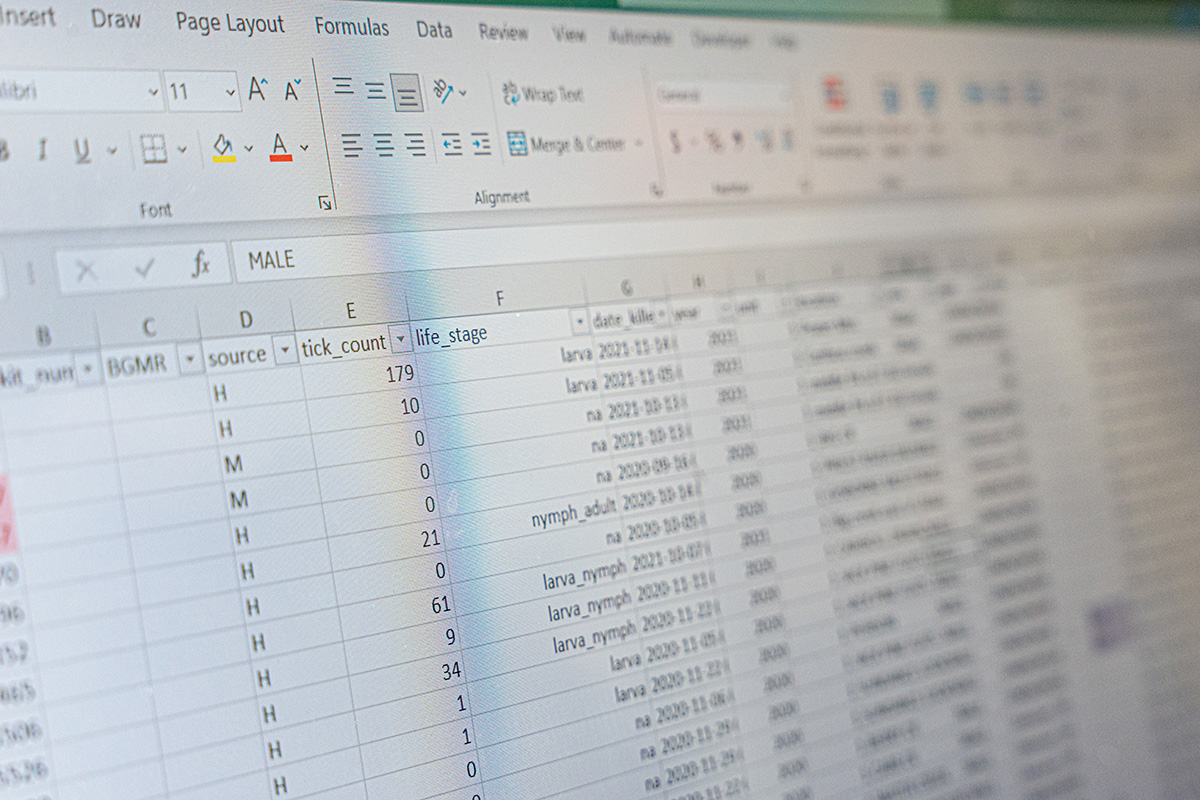

A couple summers ago, Robenstein worked in conjunction with Idaho Fish and Game, which provided her with a seemingly endless number of hide samples from the hind quarters of harvested moose. The samples came from animals killed by hunters or natural mortalities. Robenstein’s job was to count the number of ticks, adults and juveniles, from tiny clingers to large, blood-gorged parasites.

I didn’t even think about turning down the chance to participate in this research. Riley Robenstein, Junior. Wildlife Biology

Like the hides, the ticks were frozen, although some of them seemed to come alive under Robenstein’s rubber gloved hands as she carefully combed through the moose hair. “After work, I would tell my mom and dad, ‘Geez, you wouldn’t believe the number of ticks I counted today!’” she said. Her family, none of whom are biologists, were semi-aghast.

Janet Rachlow, Ph.D.

Professor of Wildlife Ecology

"I thought it was pretty disgusting and laughed a little when she wasn't able to eat things like grapes in the beginning because it reminded her of the ticks,” Robenstein’s mother, Valerie, said. “I washed her work clothes separately from the rest of the laundry.”

According to sampling data, Robenstein learned that three areas in Idaho including a piece of the Panhandle, an area west of Yellowstone National Park, and an area in southcentral Idaho along the Utah border had the highest tick counts.

“Tick counts varied across Idaho with significant differences between the north and north Central regions,” Robenstein said.

Few ticks were found on hide samples from moose taken near the Panhandle’s eastern border with Montana compared to moose taken along the Washington border. The highest count came from Island Park near Yellowstone and from moose hides along the Utah border, she said.

Robenstein presented her findings at the Idaho Chapter of The Wildlife Society in Coeur d’Alene in March.

The next phase of the research hopes to evaluate temperature and humidity during the summer quiescent period and temperature, humidity, and snow during the fall questing period when ticks emerge and look for mammal hosts, she said.

The tick research may not have been anticipated, but Robenstein said the experience has transformed her vision of future research.

“Oddly, I didn’t even think about turning down the chance to participate in this research,” she said. “I was already working on a piece using photographs of cows to quantify hair loss. I think I knew that this field comes with some very strange experiences. Now, any time I get to see a winter tick - dead or alive - I become more excited than a child eating ice cream!”

Robenstein said she never doubted that she would one day attend college in Moscow.

“My dad and mom and grandparents all attended University of Idaho, so I knew I would come here after high school,” she said.

Janet Rachlow, who oversees moose and tick research at U of I said winter ticks have substantial impacts on health, reproduction, and survival of moose calves in other populations, but scientists know less about their effects here in Idaho.

“Information about how tick loads vary across regions of the state and across years, and how weather might influence tick loads across years, will contribute to an understanding of winter tick ecology in Idaho,” Rachlow said. “This researcher helps inform managers about the potential severity of the issue for moose in Idaho -- both of which are key to developing strategies to mitigate ticks impact on moose.”

Valerie Robenstein, a nutritionist in Boise, may be creeped out by her daughters chosen field – at least the present research – but she admires her daughter’s “stick-to-it-ness.”

“I am really proud of Riley for her work ethic and commitment to the research- I can't think of many people who could stomach that task!" she said.

Article by Ralph Bartholdt, University Communications

Photos by Garrett Britton, University Visual Productions and Ralph Bartholdt

Published April 2024