Psyllids

Pest Common Name

- Potato/Tomato Psyllid (Bactericera cockerelli)

- Potato

- Tomato, pepper, eggplant, other crops in the nightshade family

- Matrimony vine, bittersweet nightshade, ground cherry, other non-crop plants and weeds in the nightshade family

Adult psyllids are approximately 5/64-1/8 inch (2-3 mm) in length, about the same size as an aphid. In form, adults resemble small cicadas. Newly emerged adults are light brown to yellow green in color, but they darken in just a few hours.

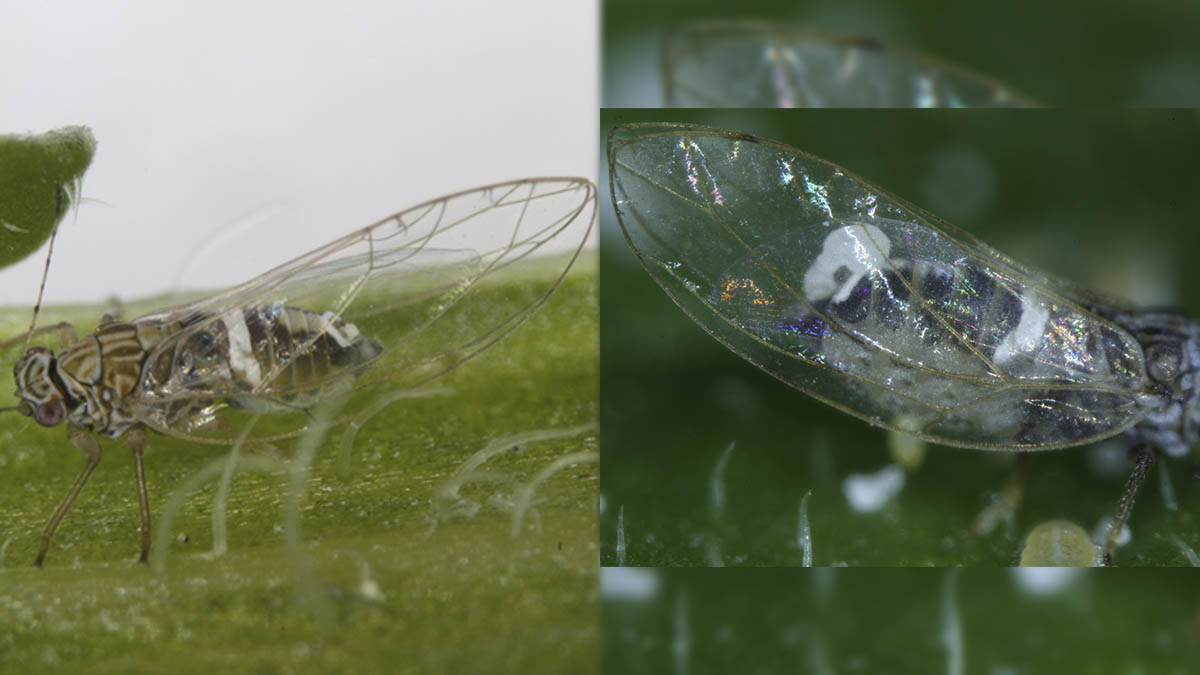

Adults can be distinguished from aphids by their lack of cornicles, the small, rear-facing, “tailpipe” like appendages near the end of the abdomen of aphids. Furthermore, they tend to jump when disturbed. In Idaho, potato psyllids can be differentiated from other psyllids by the presence of a white margin on the top, front of the head. They also have clear wings with a two-branched (not three-branched) split in the wing venation toward the base of the wing (Figure 1). A 10x lens is useful in differentiating psyllids from aphids, and for differentiating potato psyllids from other species.

Psyllid nymphs go through five growth stages (instars), ranging from about 1/64-5/64 inch (0.5-2 mm) in length (Figure 2). They have flattened, oval shaped bodies, no wings and range in color from light brown or orange when newly hatched to yellow green in later instars. In general, psyllid nymphs become progressively greener as they mature. The small size, greenish coloration and limited movement can make infestations of psyllids hard to see. In rare cases, the sugary excretions of psyllids known as psyllid sugar can accumulate on leaves below the infestation.

Eggs are orange-yellow and elevated off the leaf surface on fine stalks but are so tiny as to be barely visible with the naked eye.

Biology

A female psyllid can lay hundreds of eggs. Psyllid eggs are laid on stalks attached to leaves of host plants. After about a week, nymphs emerge from the eggs and begin to feed. Nymphs most often feed on the undersides of leaves located on the upper third to half of the plant. Usually nymphs pass through their five instars in two to three weeks before emerging as adults. Each growing season will see multiple, overlapping generations of psyllids.

Damage

Psyllid feeding can directly cause damage to plants when abundance is extremely high. Damage from feeding is called “psyllid yellows” and manifests as chlorosis (yellowing) and upward curling of new leaflets. This damage is thought to be caused by the toxic saliva that psyllids inject into the plant while feeding. However, psyllids are most often of concern due to their ability to transmit pathogens, most notably the pathogen that causes zebra chip disease (ZC).

ZC is caused by the bacterium “Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum.” Aboveground symptoms in potato may be minimal and include yellow or pink discoloration in foliage, and often are easily mistaken for nutrient deficiencies or for other diseases. Symptoms within tubers are more severe, with light brown, necrotic striations forming in the flesh. These striations become significantly darker when the potato is fried. Severe infections, especially early in the season can lead to plant death. Plant infection within one to two weeks before vine kill can still result in tuber symptoms at harvest, with some symptom development during storage.

Monitoring

The University of Idaho, in collaboration with crop consultants, maintains a potato psyllid and ZC monitoring network in commercial potato fields across the state. Traps are deployed and retrieved weekly, and psyllids are counted and tested for the presence of the bacterium that causes ZC. Results and recommendations are posted on the monitoring website throughout the season.

If you would like to monitor for potato psyllids, consider using yellow sticky cards. These traps, which capture adults, should be deployed no later than mid-May in Idaho and collected on a weekly basis. To deploy traps, place lath stakes about 10 feet (3 m) from the field edge. Remove wax paper from both sides of yellow sticky card and binder clip it to the stake just at the top of the canopy. Remember to move traps up or down to ensure they remain at the top of the canopy as plants grow or senesce. When retrieving traps, re-adhere waxy side of the paper covering to the card face.

Video — Proper use and deployment of yellow sticky cards to monitor potato psyllids

To monitor nymphs and eggs, collect 10 mature leaves from the upper third of 10 different plants located near the edges of fields. Use a hand lens to look for nymphs and eggs on the undersides of the leaves.

Management

Primary Management Tactics

Psyllid monitoring information should be used to inform management decisions. Insecticides remain the primary means of potato psyllid management. However, to avoid flaring psyllids, limit use of broad-spectrum insecticides (e.g., pyrethroids, carbamates, organophosphates).

Biological

- Limiting the use of broad-spectrum insecticides can protect natural insect predators of potato psyllids, such as minute pirate bugs and damsel bugs

- In greenhouse production some fungi, notably Isaria fumosorosea and Beauveria bassiana, may infect and help control potato psyllids

Chemical

- Apply insecticides based on potato psyllid and Lso monitoring information. No formal thresholds exist, so make application decisions based on your level of risk aversion

- Select an insecticide that targets the psyllid life stage or stages (adult, nymph and/or eggs) present and consider the other insect pests the selected product targets to maximize the efficacy of your insecticide program

- Chemistries that alter feeding activity are expected to reduce Lso transmission. These include abamectin, pymetrozine, cyantraniliprole, sulfoxaflor and tolfenpyrad

- Avoid applying pyrethroid, organophosphate or carbamate insecticides for potato psyllid control as these insecticides can cause populations of potato psyllids, aphids and mites to flare

- Avoid foliar neonicotinoid applications if this class of insecticide was used at planting or at hilling. Repeated applications will promote development of resistance in potato psyllids as well as other insect pests

- High risk fields (based on monitoring information) may require insecticide applications through the end of the season

- Recommendations for pesticides to use in the management of potato psyllid can be found on the PNW Pest Management Handbooks website

Further reading

Pesticide Warning

Always read and follow the instructions printed on the pesticide label. The pesticide recommendations in this University of Idaho webpage do not substitute for instructions on the label. Pesticide laws and labels change frequently and may have changed since this publication was written. Some pesticides may have been withdrawn or had certain uses prohibited. Use pesticides with care. Do not use a pesticide unless the specific plant, animal or other application site is specifically listed on the label. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets and livestock.

Trade Names — To simplify information, trade names have been used. No endorsement of named products is intended nor is criticism implied of similar products not mentioned.

Groundwater — To protect groundwater, when there is a choice of pesticides, the applicator should use the product least likely to leach.

- Erik J. Wenninger, University of Idaho

Desiree Wickwar, Entomologist, IPM Project Manager

Erik J. Wenninger, Professor of Entomology, IPM Coordinator

2023